I chose to upend my entire life as I knew it the day I flew into Madrid to attend school abroad for four years. Everything was new to me: the city, the country, the school, the people. However, there was one thing I was not ready to let go of: figure skating.

For 11 years, figure skating was arguably my only personality trait. I spent at least four days a week at the ice rink, moved my high school schedule to accommodate early morning practices and spent hours individually gluing 10,000+ crystals onto each one of my dresses. I was a “rink rat.” The ice was my second home.

A “rink rat” goes to Spain

The summer of 2021 was bittersweet: a decade of figure-skating competitions and memories were coming to an end. I thought I’d never see that day come, but it all crashed in when I finished my last performance to a Billy Joel medley of Vienna, The Entertainer, and It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me. Sure, I had finished my competitive years as a figure skater, but who said that I was going to let a 5,000-mile transatlantic move stop me from finding a rink?

Turns out, my lack of Spanish speaking skills was going to try and stop me – that, and the scarcity of winter sports in a summer-centric country where fútbol rules.

Many students experience some form of culture shock when they move to a new country – the food, the weather, the transport. But for me the greatest culture show was the fact that there were hardly any skating rinks in Madrid – let alone one open in September.

Many people remember figure skating only during the Winter Olympics, but this sport does not care if it’s December or the smack-dab middle of July; training goes on year-round, non-stop, all the time. During my first month in Madrid my freshman year, my priority was finding a skating program to join. But with little knowledge of the Madrid skating scene even less knowledge of Spanish, it was difficult. After much research, I eventually found an ice rink in Palacio de Hielo, or Ice Palace, a mall located in the Canillas neighborhood by the Madrid airport. Didn’t sound promising, but I’d take it!

With the help of a Spanish speaking friend and many SpanishDict translations, I managed to figure out that the rink was meant to open in early September. So on a breezy September morning, I packed my bags with my skates, hard guards and anything else I would need to survive a session on the ice. As I took the 45-minute metro ride to the rink, thoughts flooded my head: What if the website was lying and there wasn’t a public session that day? What if I scare everyone on the ice by speeding past them? What if I sound like an idiot trying to get one admission ticket?

Well, the rink was, in fact, not open that day. I still got a small glimpse of it-it was not some pop-up Christmas attraction but an Olympic-sized rink founded by 2018 Olympic bronze medalist Javier Fernandez.

Skating withdrawal sets in

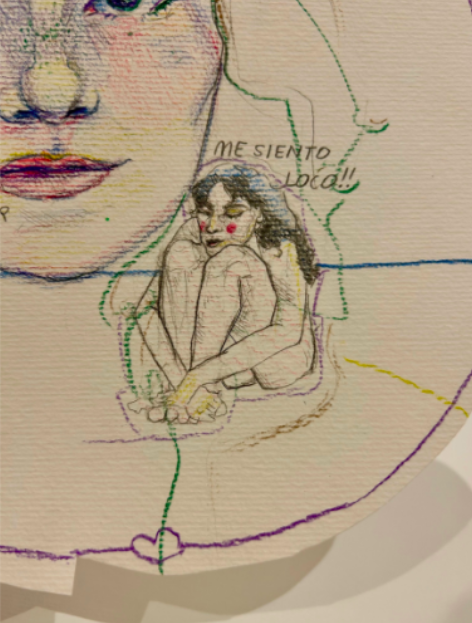

At this point, I could feel myself spiraling into a skating withdrawal. I tried the rink two more times, but it stayed closed the entire month of September. Each attempt to skate made me feel worse: skating was supposed to be my “safety blanket” while adjusting to Spanish life.

It reached a point where I sat on the floor in Palacio de Hielo, next to the rink entrance, crying.

More hours of rabbit-hole digging and empty answers later, I finally found a rink that was actually open in the month of September in the Madrid suburb of Majadahonda. At that rink, I rehearsed what I was going to say 30 minutes before I mustered up the courage to ask for a ticket. The ice was choppy, but it was enough to temporarily subdue my deep-rooted need to have knives strapped to my feet for fun.

The only downside? Public sessions wouldn’t let me maintain my current skill set. They have safety protocols to make sure that competitive figure skaters don’t kill the people there for fun. That meant I was not allowed to jump, and only could do spins in the center circle of the ice.

“Double jump” in Spanish?

At last, one full month after Palacio de Hielo said the ice rink would be open, I could finally go skating there! I told the program directors in broken Spanish that I could do a handful of double jumps, which require two rotations in the air.

I got the green light to take a “test” class. When I arrived I spent 30 minutes mentally debating whether to get on the ice or not. One phone call home and a nervous breakdown later, I finally made my way to the entrance onto the ice. By some miracle, I was noticed by the coach.

I was told to try the skills that the group was currently working on, but my anxiety threw my entire body off kilter. The group was at my level, but my nerves made it impossible for me to do anything correctly.

The coach instructed me to attend a different class at a different time, and the next week I found myself in a group lesson with other adult skaters, twice or even three times my age. But who was I to complain? The coach was the sr the adult class as well. We created sort of a bond by this point and asked me where I was from. I told him that I was from Colorado, and anyone familiar with the figure skating world knows why Colorado is so important in the sport (Hint: it’s where the Olympic Headquarters are!).

Immediately after my response, he abruptly stops the class to introduce me to everyone else. He jumped straight into the fact that I was from Colorado and trained in the Broadmoor World Arena, which is where Team USA figure skaters go to train. Disclaimer: I never trained at the World Arena, nor was I ever on Team USA. I just rolled with the punches.

I finally had a consistent enough skating schedule to help ease my transition into living in Madrid and was able to keep up the skills I spent years perfecting before the big move across the world.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from years of figure skating, it’s that falling down means one thing: you have to get back up.

And that’s what I did.