With her headphones in, listening to “Pretty Isn’t Pretty,” by Olivia Rodrigo, Zoe Hartman refreshes her Instagram feed as she sits in her Environmental Biology lecture hall awaiting class to start. Her jaw drops when she sees the post by the woman singing in her ear.

“She was literally giving out birth control at her concerts,” said Zoe Hartman, 20, from Denver, CO. “I just think it’s so cool that she’s taking such a stance and she has multiple Grammys.”

Rodrigo, 21, was temporarily giving out emergency contraceptives and condoms at her concerts during her Guts tour. A bold move, Hartman thought, considering the rocky state of reproductive rights in the U.S.

Rodrigo isn’t the only one taking bold moves. Chappell Roan performed in drag in front of record crowds. Sabrina Carpenter shocked her fans with risque lyrics and onstage presence. Charli XCX became the face of the Harris-Walz campaign.

These women are becoming Gen-Z’s new idols, contradicting societal norms unapologetically. They are Girl Pop–music made by women for young women, instead of trying to be universally palatable.

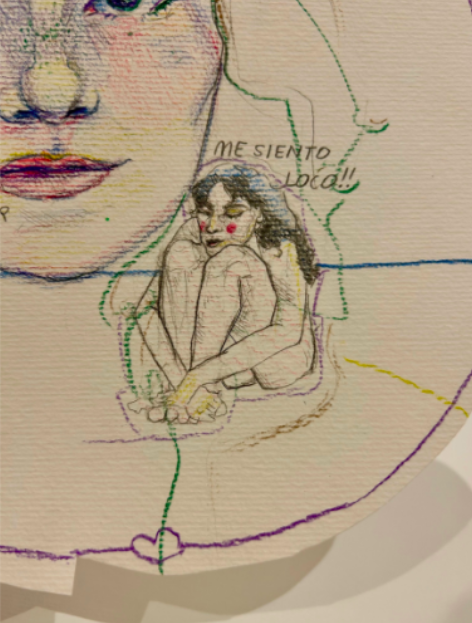

Guts and the music of other female artists explore topics like queerness, female sexuality, defiance, mental health, young adulthood, and social change.

A tweet by Charlie XCX that read “Kamala IS Brat,” a concept understood by her fans, led to her collaboration with the Harris-Waltz campaign. Political involvement is becoming the norm for artists through social media. Alex Bannworth, a study-abroad student and music fanatic, was elated to see the Brat aesthetic in politics.

“Definitely a Brat summer for me,” said Bannworth. The artist defined “Brat” as someone who has a “pack of cigs, a Bic lighter and a strappy white top with no bra,” reported CTV news. Brat celebrates not taking yourself too seriously and embracing imperfection.

Bridget Albers, a study abroad student from Oregon, reads lyrics to her favorite Brat track, “I Think About It All the Time,” as she walks to class.

“Charli wrote this song about getting older and watching people settle down. While I’m not at that point, I relate to the constant feeling of running out of time,” said Albers.

Isabel Seeney, a study-abroad student from the University of Delaware, recalls finding meaningful music for everything from breakups to birthdays.

“Women have a larger platform to express their full femininity, without shame, because it allows them to connect with a larger audience of females who relate,” said Seeney.

Why is this happening?

“The cultural conversation is more interested in female sexuality and feminist causes, and Girl Pop has become a medium for that,” said Charles Bresler, 20, a music major from Chicago, IL. Bresler listens to Girl Pop while working out.

“Me and my dad love Chappell Roan. Her stuff is super fun but still serious art with serious messages,” said Bresler.

The percentage of award-winning female albums, songwriters, and producers has been steadily increasing over the past decade, according to Billboard.com. Sophie Anderson, 21, a study-abroad student, recalls the first time she heard Sabrina Carpenter’s album Short but Sweet.

“The past few years of pop feel different. I can relate to new music a lot more,” said Anderson.

Chloe Meuhlemer, 21, from Kansas City, MO, listens to artists like Lana Del Rey and Ariana Grande on her metro commute.

“Regardless of the message, it’s just really catchy,” said Meuhlemer. “It used to be embarrassing if you liked mainstream pop, but now it’s this fun girly thing.”

The shift from Girl Pop as a “guilty pleasure” to mainstream is exciting for fans and for women who see authentic womanhood expressed in the media. Bannworth recalls how Megan Thee Stallion’s album Traumazine, which tackles mental health, helped her through tough times.

“Girl Pop is empowering and validating,” said Bannworth. “I listen to it when I need my confident, powerful energy back.” Traumazine was released after the artist’s Coachella headline and her bachelor’s degree completion in health administration, according to Billboard.com.

While many Girl Pop artists confront difficult topics, some do so more straightforwardly. Chappell Roan, the VMA’s “Best New Artist,” made an Instagram post addressing public boundaries.

“I don’t understand star culture. It makes artists feel like property just because they’re famous,” said Roswitha Zahlner, a Gender Studies professor.

Roan compared her situation as a new celebrity to that of a woman in a short skirt—just because she wears it doesn’t mean she deserves harassment. While some fans agreed with Zahlner, others criticized Roan online.

“They are artists for themselves and nobody else,” Zahlner said.